Regular readers of the bestiary may have noticed a gap in coverage when it comes to South America, the only continent we’ve not yet visited on our tour of the biscuit-eating world. I’ve been wanting to write about a Latino biscuit for a while now and what better species to begin with but the Alfajor? To my delight I found they were being sold in not just one, but two, establishments right up the road from me. Yes, my Peckham neighbourhood has no less than two Argentinian cafes along the foodie-fare that is Lordship Lane, each of them selling traditional and novelty Alfajores.

So what is an Alfajor, I hear you ask… These amazing sandwich biscuits are a cornerstone of South American cuisine and the product of a complex culinary journey from eighth-century North Africa to medieval Spain to early modern South America in the wake of the Moorish and then the Spanish empire-building that took place over the medieval and Renaissance periods. Centuries after they reached South America in the sixteenth century (in the conquistadors’ saddlebags?) the Argentinians added a special twist to their Alfajores in the form of the Dulce de Leche filling. Different regions and countries of South America continue to develop their own versions of this popular biscuit. They are so popular in Argentina they even have their own national day.

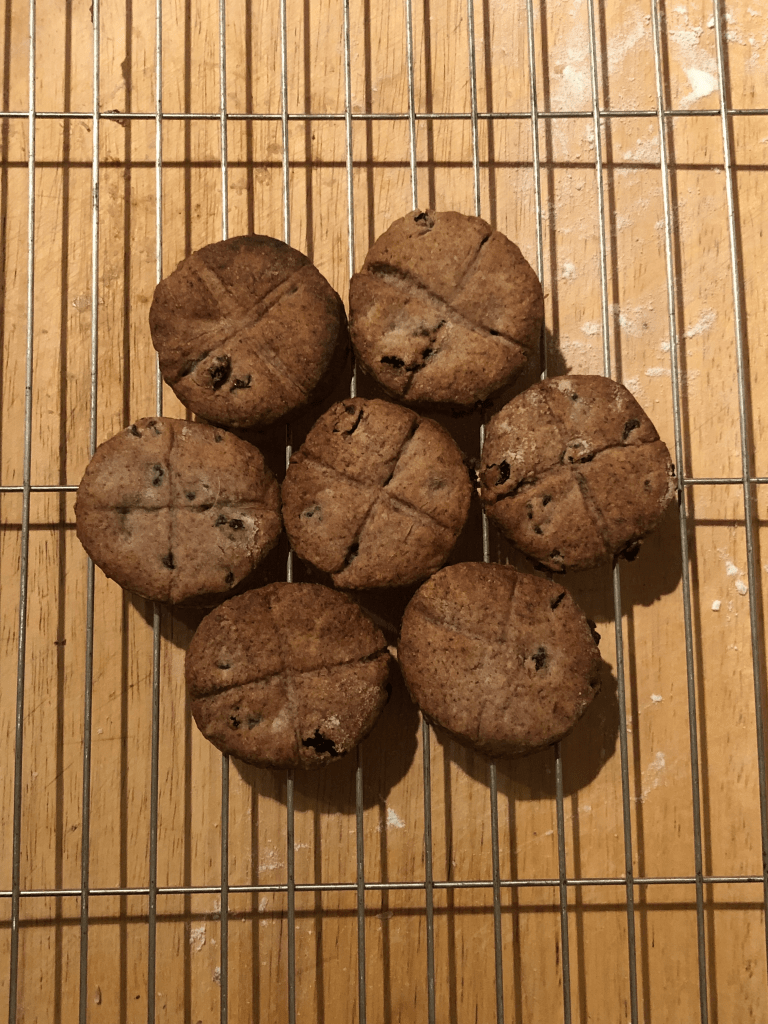

Chacarero was the name of the first cafe I visited way back at the beginning of Advent and they sell both the traditional Maicena Alfajores and Brownie, Coconut, and Chocolate-Orange and Hazelnut flavoured ones, all with the Dulce de Leche filling. After I’d waxed lyrical about Alfajores as a food group, my friend Gill and another friend who remembered them from her time in Peru went on an expedition to Lordship Lane and brought me back a novelty gingerbread-flavoured one. ¡exquisito! I ventured out there the next day and bought three others before trying Chango a little further up the street on the other side. I bought two more modern chocolate versions from the latter before treating myself to a coffee in their cafe and was touched by their generosity when the staff brought me a free traditional Alfajor to have with it. These biscuits are so rich, even for a seasoned biscuit-eater, one really is enough for one sitting, but it was a lovely treat with my cappuccino. I’ve never come across a sandwich biscuit this soft and sweet before. I’d first hit on the idea of writing about Alfajores on seeing they were the December recipe on this year’s Bake Off Calendar, but these felt more authentic than anything I could have baked.

Alfajores de Medina Sidonia are still made in Andalusia today and seem radically different to the South American versions, so much so that there is some debate whether South American Alfajores are in fact related to the biscuits first mentioned in Spanish texts after the Fall of Granada, the ones made with breadcrumbs, nuts, honey and spices. The best explanation I could come up with is that the first were the inspiration for the second and more of a creative adaptation than a direct translation into South American culture. I learned from British-Argentinian chocolatier Sur’s blog that different Alfajor recipes have their own followings in Argentina and while they are appreciated all year round, they are traditionally eaten at Christmas.

The name alfajor comes from the Arabic al-hasu meaning “stuffed” or “filled” and this reminded me of one particularly poignant line from the Virgin Mary’s Magnificat, her song in praise of God recorded in Luke’s gospel at the time of her visit to her cousin Elizabeth: He has filled the hungry with good things. (Interestingly, any public display of the Magnificat was banned in the 1980s by the Argentinian military junta after the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo placed it on posters in the capital. Mary’s declaration that God acts to cast down the proud and exalt the lowly clearly touched a nerve.) We often think of Christmas as a wonderful time of giving (and it is) but theologically speaking, it is a more wonderful time of receiving in which the abundant fullness of the Alfajor serves as a reminder that we’re blessed when we come to God with our lack.

And here we touch on something of the mystery of the Incarnation. These themes of riches and poverty, fullness and emptiness, come together most strikingly in the Christmas story. The twentieth-century German theologian Helmut Thielicke, one of the few who dared to preach against the doctrines of the Nazis, said that the story of Christ’s birth is like a melody of two parts: the lower register expressing the humbleness of Jesus’ origins as a Jewish baby with no better place to be born than an outer room which doubled as an animal shelter on account of the crowding in Bethlehem where his mother and her fiancé had been forced to travel for a Roman-imposed census. But in the line above, to borrow a sentiment from commentator Gary Roth: “angels sing hallelujahs. Hallelujahs that remind us that whatever the sadness, despair or hopelessness felt on Earth, there is also this upper register where the angels still sing over our lives and heaven remains open.”

St Paul wrote movingly of Christ as the fullness of him who fills everything in every way and of the grace that so motivated the son of God that he became poor for our sake so that through his poverty we might become rich. Because in the final analysis, as the story of the Incarnation shows, all we have to offer God is our poverty. Every blessing we receive, material or spiritual, comes from Him: the one who joyfully exchanges our emptiness for His fullness and our rags for His riches.

Further Delectation

A BBC Good Food recipe for Alfajores if you’re brave enough to have a go at making some (or, to carry on the South American theme, some Mexican hot chocolate!)

Some gorgeous embroidered Opus Anglicanum tapestries of the nativity which was famous for needlework in Europe in the high middle ages.

Some music that’s almost as revolutionary as the Magnificat…

If you would like to see more entries more regularly and help keep this bestiary free of ads, you are welcome to contribute to the Biscuit Jar.