Yorkshire being the cake capital of the world, I have struggled to find a truly Yorkshire-bred biscuit but there are some excellent contenders at Botham’s Bakery in Whitby. The ‘Betty’s of the Yorkshire Coast’ and start-up of Victorian entrepreneur Elizabeth Botham, the bakery is famous for its lemon buns, but they do nice biscuits too. On my last visit North it was their Coconut and Stem Ginger biscuits that caught my eye with their unusual ingredient base of coconut, ginger and lime, inspired by Captain Cook’s voyages of discovery.

Along with St Hild and Count Dracula (!), Cook was one of Whitby’s most celebrated residents and one part of his biography that is less commonly remembered was his success in keeping his crews for long voyages healthy. Cook was one of the earliest winners of the Royal Society’s Copley Medal due to his work in combating scurvy by adding supplements of cress, fermented cabbage and orange extract to his sailors’ diets. While I’m not sure how healthy this biscuit he inspired is, it certainly tastes fantastic. My favourite of 2025 so far and it’s suitable for vegans too as it uses plant oil rather than butter.

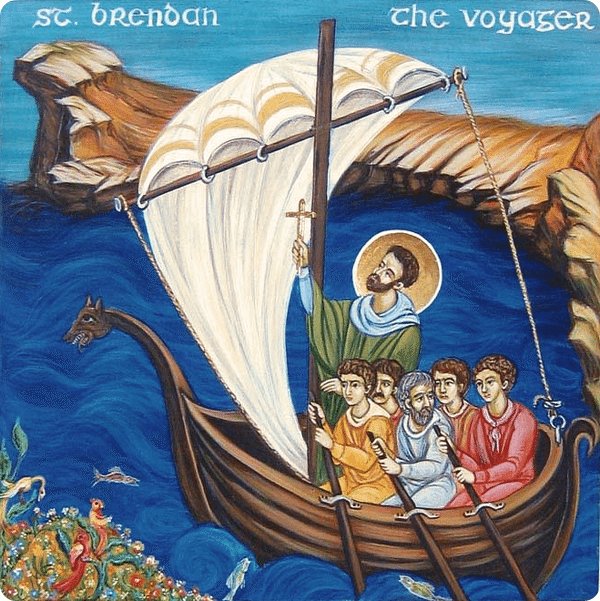

The ginger and the coconut flavours work surprisingly well together and like any decent sea-faring biscuit, they tasted even better after being exposed to the elements for a week. And if I had been paying more attention to the church calendar, I might have opened the biscuits for the feast of St Brendan of Clonfert earlier in the summer, who is also known as Brendan the Voyager or Brendan the Navigator. The 9th-century classic Navigatio sancti Brendani abbatis (or Voyage of St Brendan the Abbot) is worth a read if you’re at all interested in the lives of the early Celtic Saints and their peregrinations. As Michael Mitton writes in his tribute to Celtic Christianity, Restoring the Woven Cord, the work itself is a “highly embellished… [travelogue but] behind the parables and hyperbole, you discover a group of wonderfully open travellers who come upon small communities of monks, encountered the wonders of icebergs and great whales, and travelled vast distances in their fragile coracle.“.

Brendan and his companions had a clear objective in their wanderings. Their imagination had been stirred by stories of a mysterious blessed isle in the Atlantic and their journey in search of it opens up Dantesque portals to heavenly and hellish experiences on the ocean as well as opportunities for fellowship with other monastic communities along the way. The idea that an Earthly Paradise, or the literal Garden of Eden, existed somewhere and you could travel to it was a familiar one to medieval readers who may have literally believed that this was so. Dante’s pilgrim gets to visit it on his journey through Purgatory and in some later medieval romances, Paradise is to be found in India and Alexander the Great is allowed a glimpse of it and given a gift – a pearl or apple – to take away.

After seven years, Brendan and his monks finally find the country they have been looking for. Hidden in the centre of a dense cloud of darkness, they arrive at an island full of light. In this Paradise they discover a land of fruiting trees, endless day-time, and a swiftly flowing river they are unable to cross. There they are met by a young man with a dazzling countenance (an angel?) who knows all the monks by name and who tells them the reason they could not find the island before is because Christ had hidden it from them in order that they might see the wonderful works of God displayed in the ocean.

The monks are allowed to marvel at the island but not allowed to stay, being instructed to sail back home to Ireland with their boat loaded with heavenly fruit and precious stones as proof of their sojourn in Paradise. For most devout medieval Christians, the joys of life on earth had nothing to offer in comparison to the joys of heaven and so the idea Paradise could be visited as an earthly outpost of heaven must have seemed even more tantalising than a Coconut and Stem Ginger biscuit…

Whether he found his way to a real Earthly Paradise or not, I imagine Brendan himself would have agreed with St. Augustine that in the end we come to God by love and not by navigation. “You will seek me and find me when you seek me with all your heart“, God tells the people of Israel (and all of us) in the prophet Jeremiah. If the temptation is to think of our forever home as a heavenly place, the Bible tells us it is, most of all, a heavenly person. And a heavenly person who is with us wherever we go and who we can reach for at any moment: “If I rise on the wings of the dawn, if I settle on the far side of the sea, even there your hand will guide me, your right hand will hold me fast.” David writes in Psalm 139, an excellent sentence for all voyagers and this adventurous biscuit.

Further Delectation

Planning a voyage to an Earthly Paradise this summer? You might want to stock up on some of Botham’s biscuits.

A free English translation of the Navigatio sancti Brendani abbatis if you fancy a read of it. (Its influence can be seen on much later fictional travelogues, such as C.S. Lewis’s Voyage of the Dawn Treader.)

Finally, this is a lovely little blog from the BL on the medieval locations of an Earthly Paradise for those who can’t afford to travel (or are simply interested in the history of all this!)

If you would like to see more entries more regularly and help keep this bestiary free of ads, you are welcome to contribute to the Biscuit Jar.

Love this!

LikeLiked by 1 person