Pentecost, like Easter, is a moveable feast, celebrated each year on the Sunday fifty days after Easter. Also called Whitsun in England, it was more of a fixture in the Middle Ages than now being one of three major Church festivals that necessitated a week off along with Christmas and Easter (and the reason for the late May bank holiday next Monday). The feast celebrates the coming of the Holy Spirit after Jesus resurrection and ascension: a gift his disciples had to wait for (‘tarry for’ in some older translations) and which happened when they were together in Jerusalem celebrating Shavuot, the Festival of Weeks. Try as I might, I have been unable to find a biscuit associated with Pentecost. Not even in Catholic countries although am grateful for Italian friends’ introduction to the wonderful Colomba Pasquale (Easter Dove Cake) which would be admirably suited to a blog about cake but which I would tremble to shoe-horn into a bestiary of biscuits.

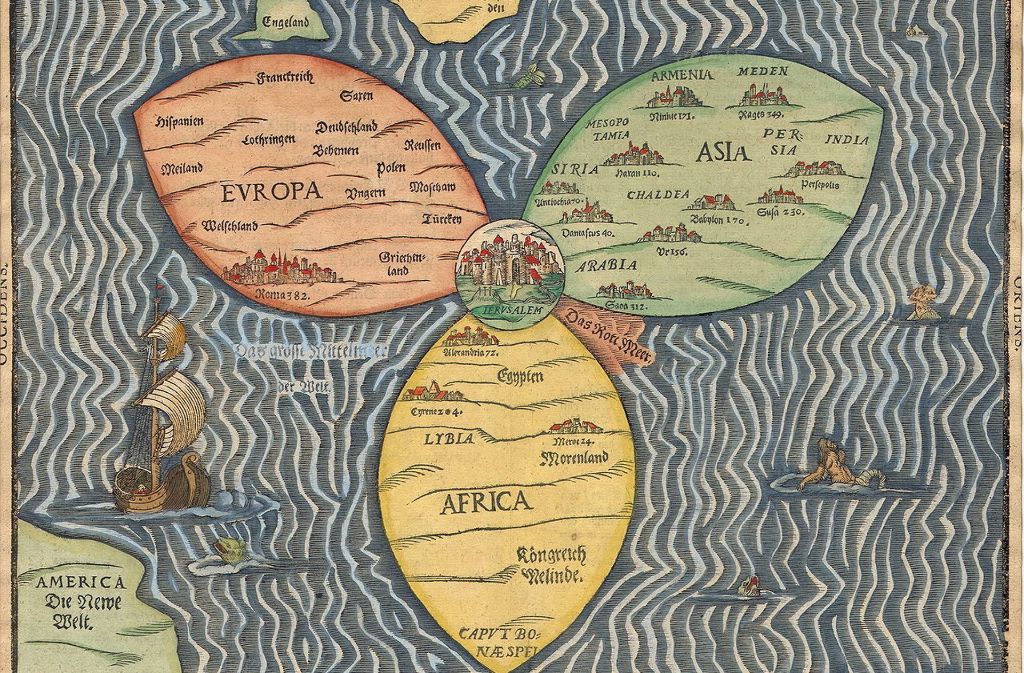

If the gentle, peaceable dove is one symbol of the Holy Spirit so too are a rushing wind and dancing flames, or more accurately something that looked like flames to the disciples in the Upper Room that first Pentecost. Luke tells us in the Book of Acts that they saw tongues of fire that came to rest on each of them and gave them the ability to declare the praises of God in unknown languages. It’s not the sort of story that sits comfortably with left-brain thinkers which may be why the Holy Spirit has remained the least known, least understood, and often sadly the least welcome person of the Trinity. The heart has its reasons that reason knows not of wrote Blaise Pascale in the seventeenth century. As a mathematician and scientist, he knew better than most how far reason can take you but it was not reason but an experience of God that convinced him of his presence on the 23rd of November 1654. FIRE, he wrote on a piece of paper he kept close to his heart sewn into the lining of successive coats. God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob – not of the philosophers and the learned.

In googling ‘fire’ and ‘biscuits’ I inevitably came across that biscuity campfire treat S’mores, which seems to me a very American thing although apparently there’s a British version you can make with Digestive biscuits rather than Graham’s Crackers. Anyway, you put biscuits, marshmallows and chocolate together in a sandwich and toast them over an open fire like so till the contents become nice and gooey:

This photo is courtesy of Unsplash, although I missed the chance to get some more bespoke pics at my home church on Sunday when S’mores and fire pits were part of the celebrations after the service, confirming my intuition that this could be the nearest thing to a Pentecost biscuit now. The name proved a bit of a mystery till I discovered it is a contraction of ‘Some More’. The first known recipe for them appeared in a Girl Scout Magazine in 1927, although it wasn’t until 1971 that people started abbreviating them to S’mores. Here is a reproduction of that original recipe, courtesy of The Daily Meal:

But is one biscuit ever enough? For me at least, it also recalls the plea of Dickens’ wretched Oliver Twist forced into a state of slow starvation in the Victorian workhouse: ‘Child as he was, he was desperate with hunger, and reckless with misery. He rose from the table; and advancing to the master, basin and spoon in hand, said: somewhat alarmed at his own temerity: ‘Please, sir, I want some more…‘ Temerity indeed as the harsh reaction of Mr Beadle teaches him not to ask for a top-up of the pitiful gruel he and the other orphans are so inadequately fed on.

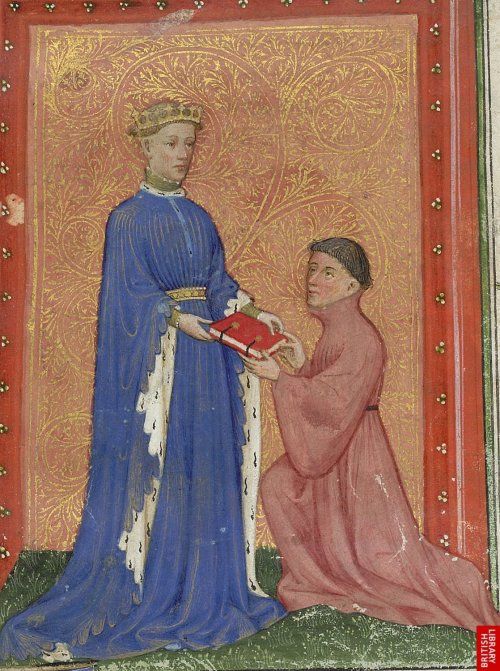

For the moral of the S’more, and asking for more, I’m still reflecting on one of the beautiful moments in the service last Sunday when one of the pastors of a neighbouring church was moved to read Jesus’s promise to his disciples the night before his death: “I will not leave you as orphans.” As their beloved teacher and hoped-for messiah, they were clearly stricken at the thought of his leaving, but it is then that he promised that God the father would send the Holy Spirit to them: God’s comforting, counselling presence who would in future live in and with them as a foretaste of that fellowship they would enjoy with him forever.

Not orphans and never alone, we can always ask God for more of his spirit knowing he is the most generous of givers. As Jesus puts it in the gospels: if even flawed earthly fathers know how to give good gifts to their children, how much more will our perfect heavenly one give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him?

Further Delectation

Some more on the history of the S’More from The National Geographic.

Some more on the art and history of Pentecost, and a beautiful rendering of an early medieval Latin hymn for Pentecost (with translation) and a rather more modern one by Fernando Ortega.

And if you still want more, here are eight incredible poems for the feast of Pentecost curated by Elizabeth Ross.

And here’s that classic “Please Sir, I Want Some More” scene from the 1968 musical version of Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1838):

If you would like to see more entries more regularly and help keep this bestiary free of ads, you are welcome to contribute to the Biscuit Jar.