I meant to post an entry before this but life got in the way. It’s still getting in the way, but I didn’t want to pass up this opportunity to write about Soul Cakes: a biscuit traditionally made and eaten over Hallowtide and almost forgotten now but which was once a regular part of this season in medieval England. I’ve been meaning to write about this biscuit for ages and received a little kick up the backside to do it this last weekend when I visited the medieval manor house of Brockhampton, which made rather a feature of them for its 600 year anniversary.

If you’re not sure what Hallowtide is welcome to post-Reformation Britain. It does have something to do with Halloween, so called because it is the evening before All Hallows Day (also All Saints Day) on the 1st of November and All Souls Day on the 2nd, both of which the medieval Church observed with a good deal more fanfare than we do now. While all Christians are called saints in the New Testament writings, there are some who are remembered with a capital S in Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican traditions for having a profound influence for good in their lifetimes and beyond. All Saints Day was for honouring these saints who had passed into glory whereas All Souls Day (an eleventh century development) was for all souls who had died in the faith. It seems likely it was about this time that the Soul Cake tradition really came into its own…

At a time where most people in England identified as Christian and believed in a literal Heaven and Hell, there was also a common belief in a place called Purgatory where souls of the departed in need of cleansing (purgation) would be sent after death to be purified before entering Heaven. The prayers of the living were believed to help speed their progress through this realm. If you were wealthy, you might have a chantry built where prayers and masses could be offered for you or your dead loved ones. If you were poor, you could visit the wealthier houses promising to say prayers for departed souls in return for a freshly baked biscuit. In the sixteenth century Shakespeare is still referring to this custom of going from house to house like “a beggar at Hallowmass”, a practice that might include games and ‘guising’ (or disguising as we say now). Souling persisted into the nineteenth century in parts of the North and Midlands despite some Protestant disapproval. It’s hard to tell whether this was for noble reasons (concern for the dead) or more, ahem, soulish ones (a love of biscuits). Here’s a lovely little clip of Sting singing a song about Souling in Durham Cathedral:

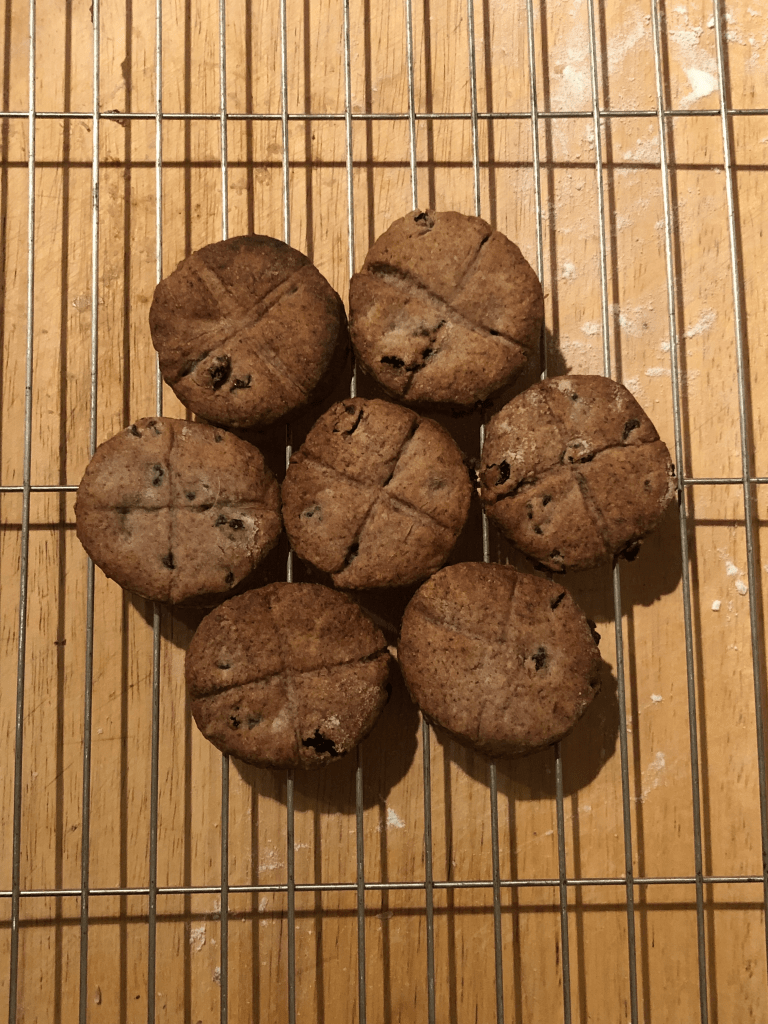

The Brockhampton estate had provided visitors with a medieval recipe for Soul Cakes which I thought I’d try on returning home to Peckham. It looked authentic as there were no measurements (always frustrating to the modern cook) so I went for pastry-like ratios of butter to flour, added the more dubious ingredients along with currants, ground cloves and nutmeg and some mixed spice in the absence of mace (another form of nutmeg). Wine and ale were included, with wine seemingly used as a mixer so I ended up using some cheap Merlot to bind it, thinking afterwards that white wine might have been better as the display cakes didn’t have the reddish tinge of mine. I used a thin wine glass to press them into rounds and marked them with a cross as instructed before trying them in the oven at Gas Mark 6 for about 12-15 minutes. They emerged pretty well cooked but didn’t seemed to rise at all in spite having a packet of dry yeast in them, but the recipe had required ‘cold’ butter and gave no time for proving. To be honest they’re tastier than I expected, even if they do taste a little like pastry soaked in mulled wine, and I look forward to offering them to any puzzled Trick-or-Treaters this weekend.

The Bible prohibits attempts to make contact with the dead through spiritualism or occultism on the grounds that doing so attracts spiritual forces of evil (the darker side of Halloween, then and now) – a very serious warning. But praying to and for the dead isn’t forbidden, even though the more reformed churches don’t believe it to be scriptural. The Anglican Church has a beautiful prayer for the departed in its funeral liturgy: O Father of all, we pray to thee for those whom we love, but see no longer. Grant them thy peace; let light perpetual shine upon them; and in thy loving wisdom and almighty power work in them the good purpose of thy perfect will… The Old English word bereft describes the experience of grief powerfully, evoking the violent theft of something precious (‘to deprive, rob, strip, dispossess’). Death feels unnatural because it is unnatural and the heart struggles to process it. It still yearns for some kind of connection between the past and the present. It still reaches out in love.

It is here the value of Hallowtide becomes apparent in reminding us of the Communion of Saints, “dead” and living. I put scare quotes around dead here because while Jesus grieved with those who mourned in this life, we find him arguing with the Sadducees who disbelieved in the Resurrection that “Even Moses demonstrates that the dead are raised… For he calls the Lord ‘the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.’ He is not the God of the dead, but of the living, for to Him all are alive.” According to St. Paul, the faithful departed are still very much in existence and part of the Great Cloud of Witnesses cheering us on. Not only are they alive with God, but in some sense they are even more alive than the living are. Whether or not they can actively help us with their prayers or we can help them with ours is just detail; the key point is that, whether we sense it or not, we are all part of this glorious Communion.

This is important because, as Norwegian bishop and writer Erik Varden says, there’s an insidious voice that likes to tell us we’re alone, but the fundamental statement of Christianity is to convict that voice of lying. Love really is stronger than death and one day God will swallow up death forever (Isaiah 25). I think that’s worth celebrating with a Soul Cake or two this Hallowtide. Blessed All Hallows Eve, All Hallows Day, and All Souls (Cakes?) Day when it comes.

Further Delectation

More information on Hallowtide and Souling traditions from English Heritage and a good short article on the post-Reformation history of Hallowmass by Professor Helen Parish.

For a quick tour through a medieval landscape of Heaven, Hell and Purgatory, Dante Alighieri is your man. For a survey of the history of Purgatory (still present in a revised form in Catholic doctrine but rejected by the reformers) see this helpful explanation.

And here’s Erik Varden’s book, The Shattering of Loneliness (recommended).

And finally, nothing to do with Hallowtide per se but my friend Paul put me on to this wonderful medievalist adaptation of Billy Joel’s We Didn’t Start the Fire by those divas at Bardcore. Very funny and very clever:

If you would like to see more entries more regularly and help keep this bestiary free of ads, you are welcome to contribute to the Biscuit Jar.