What a moving and turbulent two weeks it has been for the United Kingdom. After all the splendour and sadness of that state funeral, I think it’s high time for a cup of tea and a biscuit and as Her Late Majesty the Queen is known to have started each day in such a manner we can hardly do better than follow her example. Both her character and legacy have come into sharper focus in the shared grief of many at her passing: a vast jigsaw of memories, stories and tributes, revealing the beauty and, yes, the majesty of a life which was extraordinary by any estimation. For many of us I think there’s also been a felt grief at the symbolic passing of much we valued that she came to represent: a generation largely characterised by its sacrifice and an age largely characterised by its stability.

It’s in this spirit of gratitude and reflection that I invite us to consider the Water Biscuit. A category of savoury biscuit associated with its maker, Carr’s of Carlisle, who co-incidentally were also the first biscuit manufacturers to receive a Royal Warrant. It was an enterprising Theodore Carr who invented the Table Water Biscuit as an improvement on the Captain’s Thin in 1890. “What he did was to experiment with the thickness of this popular biscuit, trying to make it thinner and crisper, until it would seem almost like a new variety,” Margaret Forster writes in Rich Desserts and Captain’s Thin, her biography of the Carr family. The biscuit that Theodore created is basically a modern version of the Ship’s Biscuit slimmed down still further for your average landlubber. Taste-wise they’re deliciously thin and crispy, the biscuity equivalent of a pizza. As savoury biscuits, I’m pairing them with some nice cheese from Yorkshire…

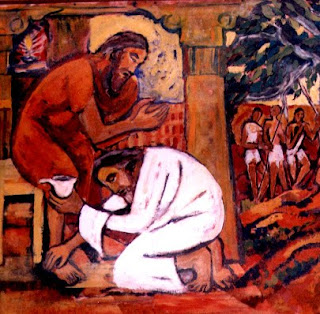

As you might guess from the name, it’s water (rather than fat) that binds the ingredients together, and helps keep the Water Biscuit fresh for long voyages on or offshore and the table refers to the meal table (or perhaps the Captain’s table if it’s at sea). To me, the association of both evokes the powerful scene from the last supper, recorded in the gospel of John:

Jesus knew that the Father had put all things under his power, and that he had come from God and was returning to God; so he got up from the meal, took off his outer clothing, and wrapped a towel around his waist. After that, he poured water into a basin and began to wash his disciples’ feet…

Washing the dirt and dust of the road from your guests’ feet and drying them with a towel was clearly servants’ work in first-century Judea and not a role the disciples had ever envisaged for their Messiah. When Peter objects, Jesus tells them: “I have set you an example that you should do as I have done for you. Very truly I tell you, no servant is greater than his master.” It was a theme he returned to again and again in his ministry: that the greatest in the kingdom of God is the one most willing to become the servant of all.

It’s a message the late Queen would have been familiar with too as a practising Christian and a teaching she clearly aimed to put into practice. As Archbishop Justin noted at her funeral, the faithful devotion to service which so characterised her long reign, (and for which, I believe, she’ll be remembered as our greatest monarch), “had its foundation in her following Christ – God himself – who said that he came not to be served but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many.”

While the manner and context of the Queen’s call to serve was both unusually public and privileged, she certainly understood the value of the contribution of the ordinary citizen to the health of the nation and with characteristic modesty believed that in the end it was just, if not more, vital to its success. The upward course of a nation’s history is due, in the long run, to the soundness of heart of its average men and women, she observed once. Like the trusty Water Biscuit, let’s cultivate such soundness wherever we can, the high watermark of which will always be our willingness to love and serve.

Further Reflection

A story about the part the Queen, her corgis, and some biscuits played in comforting a traumatised war surgeon in 2014.

An Unexpected History of Ship’s Biscuits.

The Queen’s life in her own words, although with unfortunately blurred footage. (She really did use the indefinite pronoun ‘one’ when speaking about herself and it’s nice to see some of her own wry humour coming out, and not a little brio!)

In the venerable tradition of Thomas Tallis, Sir James MacMillan set part of the passage in Romans 8 (“Who Shall Separate Us from the Love of Christ?”) to music in this eight-part a capella composed especially for the funeral on Monday. A beautiful piece – and promise – for the future: