Each time there is a royal celebration of some kind there are special tins with special biscuits. I bought such a tin for the late Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, and either bought – or was given – them to celebrate the births of Princes George and Louis, and Princess Charlotte. So as this is the first time in seventy years that Britain has had a coronation I decided to purchase a Carolean one, although it still feels odd talking about the King instead of the Queen, and no longer being a noveau Elizabethan. I teetered a bit between one of Cartwright and Butler’s solemnly splendid evergreen tins and this gorgeous purple and gold affair from Marks and Spencer’s, which was twice as sumptuous at half the price:

I’ve learned over the years that you can’t judge a biscuit by its tin, but I was pleasantly surprised at the quality of the shortbread inside. I’ve written about this quintessentially Scottish biscuit before so won’t go into the history of it again but where I was expecting some standard rounds or wheels the M&S bakers went with a regal theme, a kind of regalia in biscuit form if you will…

I’ll leave the crowns and palaces and flags to speak for themselves, but linger a moment on the symbol of the orb and cross. A distinctly medieval image, the orb alone was a Roman symbol of imperial power but for the Christian monarchs and emperors of Europe the addition of the cross over it refocused attention on Christ as the eternal sovereign of the world and the King to whom all earthly kings must be subject as holders of temporal and limited power.

This medieval view is biblical in so far as scripture talks of all earthly powers and authorities owing their positions to God, but the bible as a whole does not offer us unqualified support for monarchy as a system either. When the Israelites petition Samuel for a king so that they can be be like the other nations, God makes it clear that if they go ahead with their plans to adopt a monarchy it will place many burdens and obligations on them and that their asking itself is a symptom of their having rejected Him as the only king they need. However, once the decision in favour of a monarchy has been made and their first king, Saul, fails several crucial tests of character, God chooses his own king for his people, the shepherd boy David, and blesses his socks off, telling him he will never fail to have a descendant on the throne of Israel. All of which suggests that God is not so much pro- or anti-monarchy as he is willing to work in whatever flawed-but-capable-of-good governmental systems we find ourselves in to help bring about the coming of his own – everlasting – kingdom.

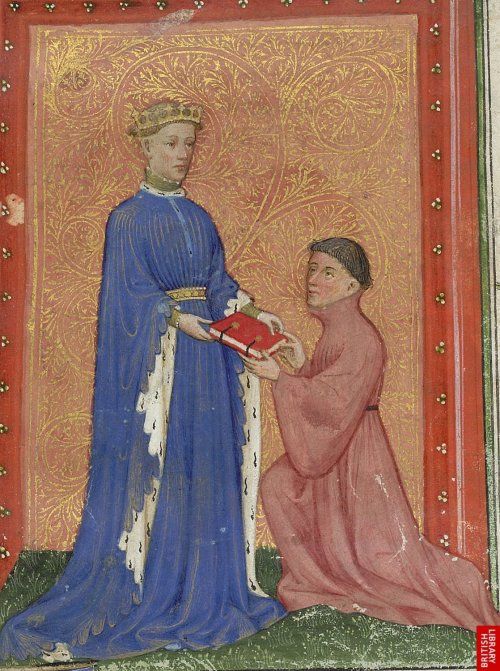

The Books of Kings and Chronicles record the deeds and characters of the kings of Israel and later of the Northern and Southern kingdoms after Solomon’s time. Some kings were outstandingly good, some were outstandingly evil, and some were fairly good or fairly evil, but for each the crucial question was whether they would worship the God of their ancestors and worship him exclusively; their success and prosperity was determined in a large part by the spiritual choices they made and on who, or what, they had set their hearts. The damage done to a nation by a weak-willed or corrupt king and conversely the good done by a virtuous one could be so great that the moral and political education of a future monarch was of the utmost importance to their subjects in medieval Europe and led to a whole genre of literature on the topic called Mirrors for Princes. Here’s an illustration of the London poet and scribe Thomas Hoccleve handing his Regement of Princes (c.1411) to the future Henry V:

The powers of a king these days are more constrained thanks to the checks and balances of constitutional monarchy but he still possesses extraordinary influence. Pace Dieu et mon droit, less emphasis is given to his divine rights than his divine responsibilities; it is the Christian ideal of servant-hearted kingship that informs the ceremony of the Coronation in the liturgy used in Westminster Abbey this weekend, where a young person (one of the choristers of the Chapel Royal) will welcome King Charles with these words:

Your Majesty,

as children of the Kingdom of God we welcome you

in the name of

the King of Kings

And he replies:

In his name, and after his example, I come not to be served

but to serve...

Just as the best earthly marriages offer our imaginations a little glimpse of the marriage of Christ and his people, so the best earthly coronations offer our imaginations a glimpse of the glory and majesty of the King of Kings and the immense dignity and significance that he gives to us as his sons and daughters. And it’s characteristic of the best earthly monarchs that they have always understood themselves as human actors in a spiritual drama, never mistaking the shadow for the eternal reality. A perspective evident in the old Wesleyan hymn sung at the funeral of the late Queen:

Finish, then, thy new creation;

pure and spotless let us be:

let us see thy great salvation

perfectly restored in thee;

changed from glory into glory,

’til in heav’n we take our place,

’til we cast our crowns before thee,

lost in wonder, love, and praise.

Tomorrow feels like more of a solemn than a celebratory moment in the life of the nation if I’m honest but one I’ll be watching with a cup of tea and a coronation biscuit.

Further Delectation

A round-up of Coronation Biscuit Tins… Good Housekeeping have produced a feature on the best ones to buy!

Following the ceremony tomorrow with your choice of coronation biscuit? Here’s a link to the service guide with all the liturgy they will be using with the bible readings and songs.

Not such a fan of thrice-gorgeous ceremony? Neither was one of Shakespeare’s best loved medieval kings. ‘Tis not the balm the sceptre and the ball... A superb rendition of one of Henry V’s monologues by Sam West.

And here’s the wonderful Porter’s Gate declaring the greater glory of the King over all:

If you would like to see more entries more regularly and help keep this bestiary free of ads, you are welcome to contribute to the Biscuit Jar.