‘Mpanatigghi are… unusual in the biscuit world. Ancestry wise, you can trace them back to early modern Sicily. If they resemble a cross between a Cornish Pasty and Spanish empanada that’s because they are far more like either of these things than a traditional (British) biscuit. Sicilian Meat Cookies is a common English translation. Dolce di carne is another Italian name for them because they’re crafted from light pastry dough, dark chocolate, winter spices, nuts and… meat. Most of the pictures of them in the wild show them folded into half-moon shapes with the chocolatey filling bursting out of a hole at the top like so:

The ‘Mpanatigghi give a whole new meaning to the word ‘sweetmeat’ (a medieval term) and if you’re thinking the dark chocolate-beef combo sounds rather Mexican I’m with you. Modica, the town associated with them, is famous for its Aztec-inspired chocolate and Sicily’s hispanic culinary influences – hinted at in the semantic roots of the ‘Mpanatigghi being so similar to the empanada – are a throwback to the days the island was under Spanish control. I found a recipe online that seemed easy so decided to have a go myself, mixing up ground beef, ground almonds, grated dark chocolate, sugar and cinnamon for the filling (I left out the ground cloves as these were hard to find). A new adventure for me and this was the funnest part:

The end results were more like sedate mini English pasties with a weirdly chewy chocolatey centre. They’re not unpleasant and you could get used to them as a picnic item, but it’s fair to say they were more an oddity than a triumph and as I was too shy to offer them to my lunch guests on Sunday I’ve spent the week eating them up. I suspect I could find better recipes online (the proportions of dough to filling in this one were a little suspect) but I won’t be making them twice. If I ever visit Modica I’d love to try some authentic ones.

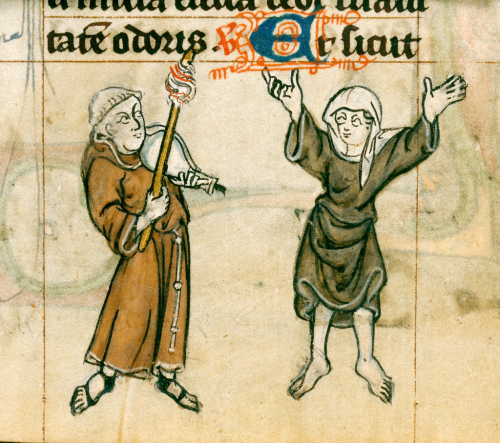

As for the moral, well, one story has it that a community of nuns in Modica first came up with the idea for ‘Mpanatigghi, slipping small amounts of ground beef or veal into their biscotti to hide among the sweet filling of nuts and dark chocolate. The point was to break the Lenten rules without observers knowing by smuggling meat into an innocent-looking, sweet-tasting biscuit. (Before modern times, chocolate, sugar and nuts could be eaten freely during Lent for those who could afford them; it was butter, eggs and meat that were frowned on.) The most sympathetic defence I’ve seen of this culinary sleight of hand is that the nuns were worried that six weeks without any red meat would have a deleterious effect on the monks and a little boost of protein would help them fulfil their preaching duties as they travelled from place to place during the fasting season!

With Ash Wednesday upon us and the dubious example of the ‘Mpanatigghi before us, it begs the question of how we should fast as much as what we should fast from. Is there a right and a wrong way to do it? The answer from the Bible seems to be yes. Jesus had strong words to say about those who made a religious show of fasting, calling them hypocrites who had already received their reward from men (impressing others) and so shouldn’t hope to receive any reward from God. He also didn’t have much time for those who in their religious practices sacrificed as little as they thought they could decently get away with, knowing that such sacrifices, like the innocent-looking ‘Mpanatigghi, were more about the appearance than reality, of conforming outwardly, and little to do with the heart.

God is all about the heart, and in Lent the discipline of fasting becomes a means of purifying and softening it. Whether as a private or corporate undertaking, it can involve giving up all food or just luxury foods (as in the medieval fast) or some other act of self-denial like fasting from social media. Along with delayed gratification, self-denial is not something our culture is all that good at and the long Lent fasts were traditionally meant as a reflection of, and aid towards, cultivating humility before God. But as Jesus’s words showed, it’s definitely possible to fast in the wrong spirit and in one surprising passage in Isaiah God gets very irritated with those whose fasting hasn’t improved the condition of their hearts at all:

Is not this the kind of fasting I have chosen:

to loose the chains of injustice

and untie the cords of the yoke,

to set the oppressed free

and break every yoke?

Sharing your resources with the needy, standing with those who are oppressed and afflicted, not stirring up strife or constantly accusing others, or exploiting your employees or turning away from family who need you… This is the kind of fasting that moves God most apparently, and without it any outward acts of self-humbling fail to impress him.

For those who do try to fast in Lent in some way, these words are challenging and liberating in equal measure. Challenging because, if we’re honest, most of us identify real gaps between our ideals and actual behaviour when it comes to practising our faith; we don’t always live up to own standards let alone God’s. But liberating because the God who is so tough on religious hypocrisy continually shows himself soft on those who admit the gaps and come to him humbly with them, asking his help to change.

Further Reflection

More on the history of the ‘Mpanatigghi and a recipe if you fancy having a go at making them (there are simpler versions out there but this looks a bit better than mine!)

’40’ a short animated film by Si Smith imagining Jesus’s forty day fast in the Judean desert:

If you would like to see more entries more regularly and help keep this bestiary free of ads, you are welcome to contribute to the Biscuit Jar.